Mamluks: Power of Ornament

Dania Khan is a Dubai-based stylist and designer, now bringing…

From Cairo’s looms to Europe’s treasuries, the Mamluks made spectacle their language, weaving politics into textiles, metalwork, and myth.

Legacy of an Empire. The title alone carries weight, a promise of grandeur, resilience, and spectacle. At Louvre Abu Dhabi, it did not disappoint. During the press preview in the capital, the museum’s director Manuel Rabaté and Laurence des Cars, President of the Musée du Louvre, reminded us that the Mamluks were more than a dynasty of soldiers, they were architects of culture, curators of exchange, and builders of identity.

Immersive Shadow Theatre Installation ; Video Source: Dania Khan

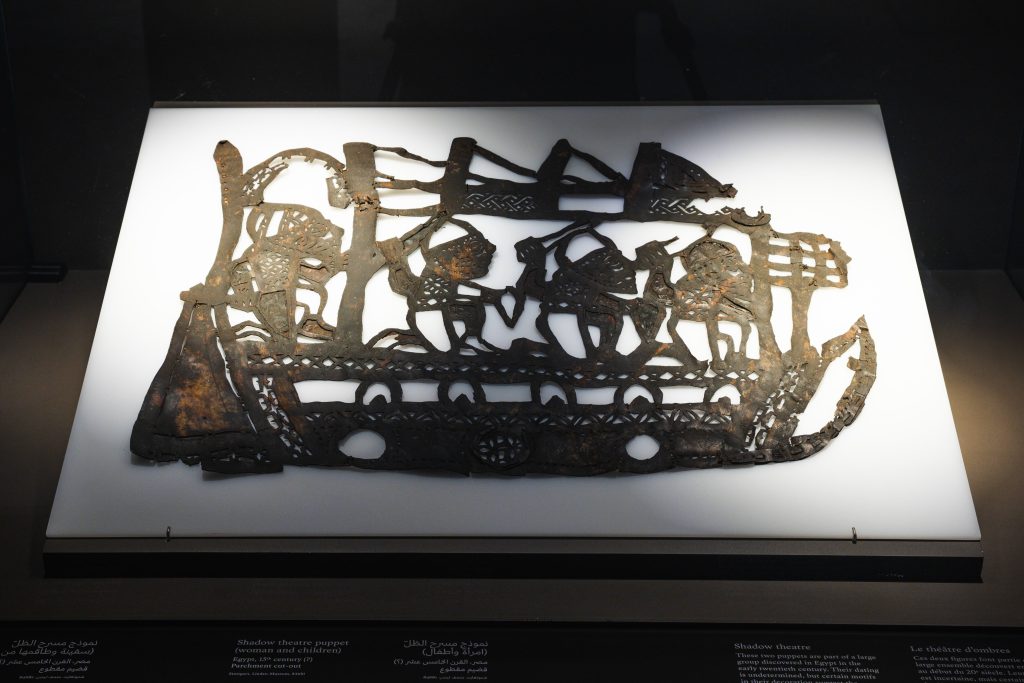

From there, we were ushered into the galleries, divided into groups, anticipation building as we walked through the corridors toward the first installation. I was glad to be led by Dr. Karine Juvin, the exhibition’s scientific curator, whose passion and clarity shaped the journey. The space darkened, the chatter fell away, and the first object revealed itself, not a manuscript or a weapon, but an immersive shadow theatre. Projected onto a circular veil of threads, the animation drew on the centuries-old art of Islamic puppetry, enveloping visitors in a 360-degree tableau of Mamluk life: armored cavalry, market scenes, fortified towers. Beneath it, horsemen rode in endless circles around a central pool motif, echoing martial symbolism and artistic style.

Shadow Theatre Puppet (Ship & Crew of Warriors) , 15th Century – Egypt; © Department of Culture and Tourism–Abu Dhabi ; Photo by Daryll Borja-Seeing Things

The choice was apt, the Mamluks were performers of power, curating their image through spectacle, ornament, and textile as much as through military might.

They were no ordinary rulers. Rising in 1250 from the ranks of enslaved soldiers, captured as boys from the Caucasus and Central Asia and trained in Cairo’s barracks, they forged a sultanate that lasted more than two centuries. Cut off from family ties and unable to establish hereditary dynasties, they built legitimacy through performance. Power was staged, in military triumphs, in architecture, and most vividly in the luxury arts.

Carpet decorated with three medallions, Second half of 15th century – Egypt, Cairo ; © Department of Culture and Tourism–Abu Dhabi ; Photo by Daryll Borja-Seeing Things

Chasuble 14th Century -Syria, Egypt or Iran; © Department of Culture and Tourism–Abu Dhabi ; Photo by Daryll Borja-Seeing Things

Nowhere was this clearer than in textiles. The khilʿa, or robe of honour, bestowed by the sultan, was not just a garment but a contract of loyalty. Tiraz bands embroidered with Qur’anic blessings or the sultan’s name acted like medieval logos, stitched into hems as declarations of allegiance. When I asked Dr. Juvin what made these robes distinctively Mamluk, she was quick to note: robes of honour were widespread. “What makes the Mamluks stand out,” she said, “are their blazons, heraldic emblems unique to them. The blazon is how you know it’s Mamluk, because it was only used by them.”

This point is made powerfully in the galleries. Silk fragments shimmer with Sultan al-Nasir’s name, inscriptions as bold as any monogram. Embroidered medallions and double-headed eagles repeat across cloth, armour, even basins, each a coded reminder of who ruled. Authority was never anonymous, it was branded, worn, and seen. Al-Jazari, the 12th-century polymath, once wrote that fashion was inseparable from identity and singled out the turban as a symbol of the Arab persona. The Mamluks understood this instinctively.

The fragments on display may be modest compared to monumental Qur’ans and luminous basins, but they carry the story of global exchange in every thread. Indian cottons printed with chevrons, crescents, and fish motifs were imported and copied in Cairo workshops. Blue-and-white cottons from Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad combined batik dyeing with Arabic inscriptions and double-headed eagles, even Chinese cloud patterns. Egyptian weavers pioneered the kabaty method, integrating decorative threads directly into the cloth, a technique admired as far away as China. And among the more curious borrowings was the waqwaq motif, a Japanese-inspired “talking tree” sprouting human and animal heads, proof that even eccentric ideas could travel and be refashioned in Cairo.

Certificate of pilgrimage (Hajj) delivered to Maymuna, daughter of Muhammad al – Zardili Arabia, Mecca (?), 836 AH/1433 CE ; © Department of Culture and Tourism–Abu Dhabi ; Photo by Daryll Borja-Seeing Things

The Mamluks, however, were not passive borrowers. As Dr. Juvin reminded us, inscriptions and blazons anchored these global influences in Cairo. Whatever their origins, the cloths proclaimed: this is Mamluk.

If they imported lavishly, they exported just as powerfully. Venetian tapestries depict ambassadors in Damascus, striped arches and red turbans recording not just diplomacy but style. In Spain, Nasrid silks modeled on Mamluk tiraz carried Qur’anic inscriptions into Iberian weaving workshops. In Denmark, a fragment of Mamluk silk was repurposed into a Christian chasuble, a golden textile reworked into ecclesiastical vestments, a cross stitched over Arabic script. “This kind of reuse is often how we preserve textiles,” Dr. Juvin noted. Further east, in sixteenth-century Poland, woven belts drew directly on Islamic patterns but were rebranded as “Polish belts,” another reminder that fashion mutates as it crosses borders.

Influence moved the other way, too. By the 15th century, Mamluks imported Ottoman velvets and Italian silks, layering them into their own repertoire. It was, as Dr. Juvin described, “a big mix,” a cosmopolitan fashion system long before globalization became a buzzword.

What struck me most, however, were not the diplomatic gifts but the fragments of daily life: cushion covers, cotton swatches, fabrics patterned with crescents and fish. Even domestic objects were staged with ornament, turning homes into backdrops of identity. Power in the Mamluk world was woven into the textiles of everyday living.

The exhibition’s strength lies in showing how textiles, basins, Qur’ans, and blazons all formed one language of identity. A robe, a cushion cover, a saddlecloth, each was a stage for ornament, each an assertion of authority. The basins, gleaming under glass, were especially striking. Their copper surfaces inlaid with gold and silver shimmered like liquid light, their decoration alive with lotus flowers, hunting scenes, polo matches, and princely gatherings. They dazzled not only by craft but by presence, heavy with symbolism, radiant with prestige.

Basin Known as “Baptistére de Saint Louis”, Signed Muhammad ibn al-Zayn C.1330-1340 – Syria or Egypt ; © Department of Culture and Tourism–Abu Dhabi ; Photo by Daryll Borja-Seeing Things

That message reached its climax in the final gallery, where the famed Baptistère de Saint Louis stood alone in its case, like a relic and a riddle. Once part of the French royal treasure, it is among the most studied objects of Islamic art in the Louvre, and one of the most mythologized. For centuries it was believed to be a crusading trophy brought back by Saint Louis himself, used to baptize the kings of France. In fact, as scholarship has shown, it was made nearly a century later in Mamluk Egypt or Syria, around 1320–1340. Its copper body, shimmering with inlaid silver and gold, is covered with motifs as cosmopolitan as its history: horsemen, vegetal scrolls, lotus flowers, and princely figures. A Mamluk masterpiece recast as a French relic, it embodies the paradoxes of cultural exchange, how objects travel, are reinterpreted, and acquire new lives in different worlds.

Leaving the galleries, past the shadow puppets and luminous silks, I thought of how fragmented the textile displays were, “bits and bobs,” as my history buff companion put it, yet how powerful their story remains. The Mamluks remind us that power is never just worn, it is performed, woven, and staged for the world to see. In a culture still obsessed with logos, spectacle, and global fashion flows, their legacy is not distant history but an uncanny mirror.

What's Your Reaction?

Dania Khan is a Dubai-based stylist and designer, now bringing her lens on style, culture, and city life to the page as a columnist for Gazetta. With roots in Abu Dhabi and a flair sharpened in London and Paris, she’s a former Elie Saab protégé on LBC’s Mission Fashion and a Lancôme Color Design Awards finalist. Her career spans couture to styling for TVCs, editorials, and music videos. She’s also a mother of two, balancing her creative chaos with homework, after-school activities, and last-minute costume days, while still chasing the many dreams she hasn’t yet ticked off. With a sharp eye and a love for storytelling, Dania’s column serves up fashion, food, and the unexpected, with a side of flair, curiosity, and unapologetic style.