Grounding Architecture: Warm Tones Redefining Built Spaces

They say fashion tells a story, but for Dina Yassin,…

Warm, grounding tones are reshaping the world of architecture, creating spaces that feel authentic, human, and deeply connected to their environments. From terracotta façades to sunlit, clay-toned walls, architects are moving away from cold, industrial aesthetics and toward designs that resonate on a deeper, more emotional level. These tones—earthy reds, soft ochres, and sandy beiges—carry a sense of place, history, and belonging, making architecture feel alive and reflective of its surroundings.

This concept is deeply rooted in tradition. For centuries, architects have drawn from their environments, using locally available materials and pigments to build homes and monuments. Ancient civilizations in Egypt, for example, used ochre and limestone to create timeless structures like the pyramids, designed to harmonize with their desert setting. Across the Mediterranean, terracotta became synonymous with warmth and durability, a material that could withstand time and tell stories of the land. Today, architects are reviving these historical practices, blending them with modern innovation to create spaces that are both timeless and forward-thinking.

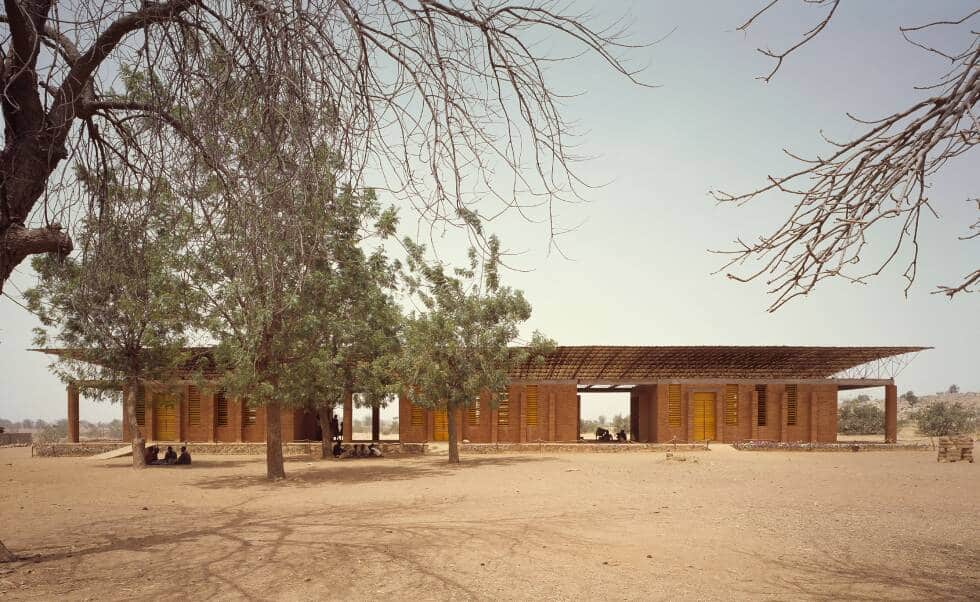

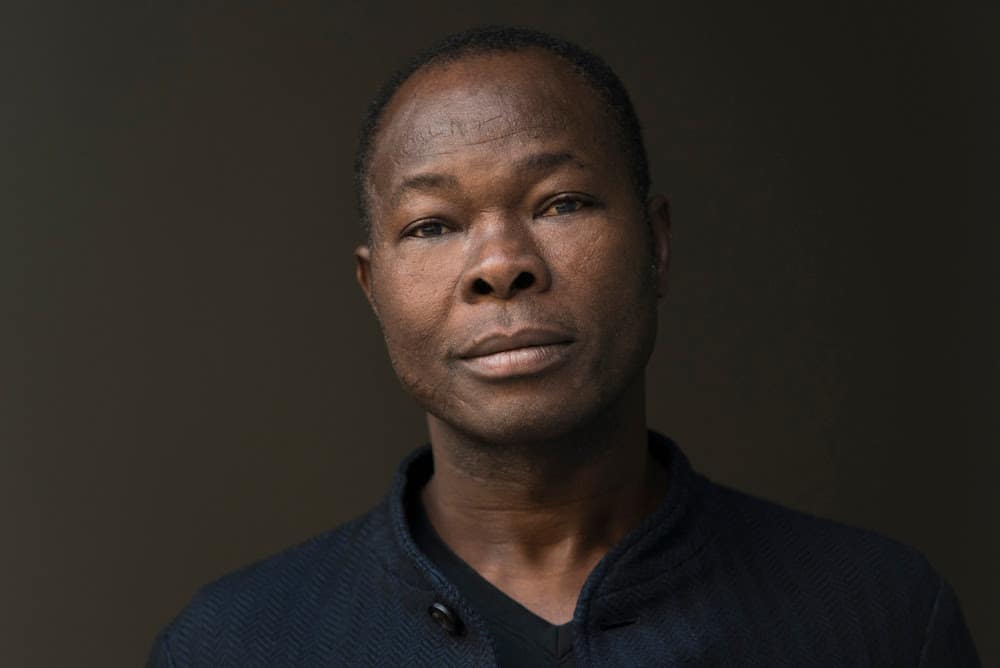

A striking example of this in Africa is the Gando Primary School in Burkina Faso, designed by renowned architect Diébédo Francis Kéré. Kéré, a Pritzker Prize winner, is celebrated for his ability to integrate local materials, cultural traditions, and modern techniques. For the Gando Primary School, he used locally sourced clay and brick, not only to ground the structure in its environment but also to ensure affordability and sustainability. The earthy tones of the clay bricks echo the warm colors of the surrounding landscape, while the building’s open, breathable design naturally regulates temperature—a necessity in the region’s hot climate. This isn’t just architecture; it’s a dialogue with the land, reflecting a deep respect for its people and resources.

Diébédo Francis Kéré; Image Source: https://www.uia-architectes.org/en/resource/diebedo-francis-kere-2/

In contemporary urban contexts, warm tones are being reimagined with cutting-edge materials like pigmented concrete. The Centro Cultural Teopanzolco in Cuernavaca, Mexico, uses warm concrete to echo ancient pyramids, creating a monolithic structure that feels monumental yet grounded. Similar approaches are appearing in African cities. In Nairobi, the One Africa Place building incorporates natural stone and terracotta accents that reflect the Kenyan landscape while offering a modern interpretation of traditional forms.

Centro Cultural Teopanzolco; Image Source: CCTeopanzolco

One Africa Place Building, Nairobi; Image Source: https://www.oneafricaplace.com/

Another example closer to tradition is the use of rammed earth in residential and commercial buildings across sub-Saharan Africa. Rammed earth construction, which compresses soil into solid walls, not only provides natural insulation but also brings rich, warm tones that integrate seamlessly into their surroundings. The Massingir Lodge in Mozambique exemplifies this approach, combining earthy walls with thatched roofs to create structures that feel like an organic extension of the landscape.

Massingir Lodge; Image Source: Massingir Safaris

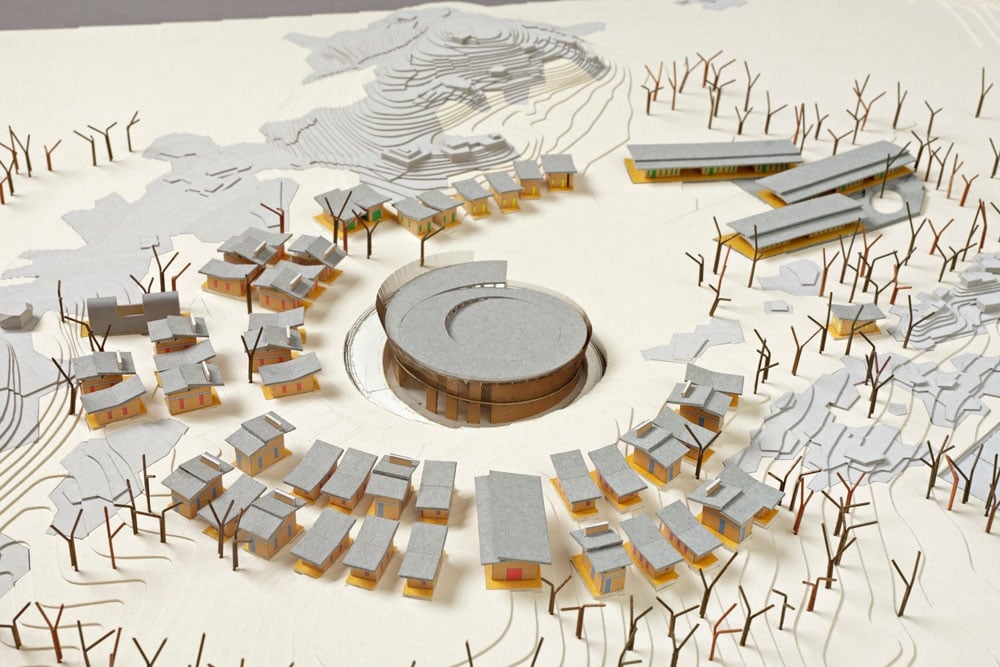

Warm tones in architecture aren’t just about materials—they’re also about how light interacts with surfaces. In Marrakech, the Yves Saint Laurent Museum incorporates warm, brick-like hues that catch and shift sunlight throughout the day, creating a dynamic visual effect. Similarly, in Burkina Faso’s Opera Village, another project by Diébédo Francis Kéré, the buildings use warm-toned clay and wood to create structures that glow under the African sun, celebrating the land and its light.

Yves Saint Laurent Museum; Image Source: YSL Museum By Frederic Aranda

Model Of The Opera Village Laongo/; Image Source: Kéré Architecture

Sustainability and grounding tones go hand in hand. Local materials like adobe, clay bricks, and rammed earth reduce environmental impact while connecting buildings to their cultural and natural contexts. The Makoko Floating School in Lagos, Nigeria, although temporary, used timber and natural tones to blend into its aquatic environment while addressing the unique needs of a community living on water. Such designs don’t just solve practical challenges—they tell stories of resilience, innovation, and respect for the land.

In urban architecture, warm tones also soften the harsh lines of modern design. The Vessel at Hudson Yards in New York uses bronzed metal to bring warmth to its futuristic geometry. Similar principles are applied in African cities where the interplay of natural materials with modern forms creates a sense of balance. Projects like the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town, housed in a converted grain silo, use concrete softened by light and texture to reflect both history and innovation.

The Vessel At Hudson Yards, New York; Image Source: https://www.hudsonyardsnewyork.com/discover/vessel, Zeitz MOCAA In Cape Town; Image Source: https://zeitzmocaa.museum

The use of grounding tones in architecture is about more than aesthetics; it’s about creating spaces that resonate emotionally and physically. These tones anchor buildings in their settings, connect them to history, and invite people to engage with them on a deeper level. They transform architecture from mere structures into living, breathing extensions of the landscapes they inhabit.

In Africa and beyond, this movement represents a shift toward designs that are sustainable, culturally rooted, and emotionally impactful. Whether it’s a clay-brick school in Burkina Faso, a desert-inspired home in Morocco, or a terracotta-clad skyscraper in Nairobi, warm tones are rewriting the rules of architecture, proving that the future of design is as much about where we come from as where we’re going.

What's Your Reaction?

They say fashion tells a story, but for Dina Yassin, it’s more than just storytelling—it’s an art, a science, and a little bit of magic. As the Co-Founder, Chief Storyteller, and Editor-in-Chief of GAZETTA—among many other titles—she’s the woman behind the words, the visionary shaping narratives, and the creative force redefining luxury fashion journalism in the digital age. With over two decades of experience in luxury brand consulting, creative direction, and trend forecasting, Dina has worked with some of the most coveted names in the industry—think Van Cleef & Arpels, Kenzo, Bvlgari, Hermès, and Chloe—all while keeping her finger firmly on the pulse of what’s next. Her work has graced the pages of Vogue Arabia, Harper’s Bazaar, Condé Nast Traveler, Mojeh Magazine, Vanity Fair, Marie Claire, 7 Corriere, and The Rake—among many other top-tier titles—solidifying her reputation as a fashion and luxury thought leader. But here’s the twist—Dina isn’t just reporting on the future; she’s creating it. Under her leadership, GAZETTA introduced EVVIE 7, an AI-driven journalist pushing the boundaries of editorial innovation. Because in a world where algorithms influence aesthetics as much as designers, Dina ensures GAZETTA stays one step ahead, seamlessly blending technology, culture, and high fashion into a platform that speaks to the modern, forward-thinking luxury consumer. Beyond her editorial expertise, Dina is a renowned luxury brand consultant, trend strategist, and creative powerhouse who thrives at the intersection of fashion, culture, and digital storytelling. Whether she’s consulting on luxury branding, forecasting emerging trends, directing high-profile fashion campaigns, or curating immersive experiences, she’s always asking the big questions—What’s next? Who’s shaping it? And most importantly, how do we make it unforgettable? One thing is certain: Dina Yassin is always at the forefront of what’s next.