What the Brush Remembers: Michael Adonai and the Art of Carrying Home

It’s funny, the things we carry with us. The smell of bunne brewing in a jebena—that smooth clay pot used in every sacred coffee ceremony from East Africa. The sound of a mother humming while shaping himbasha—a slightly sweet celebration bread known in Tigrinya as ሕምባሻ (himbasha) and in Amharic as አምባሻ (ambasha). The unspoken choreography of life under a roof that hummed with faith—even if the electricity was rarely on.

For Michael Adonai, it was never about becoming an artist. It was about trying to make sense of what already lived inside him.

“I don’t choose themes,” he says. “They find me.”

Born in Asmara in 1962, Michael’s childhood unfolded under the low sky of war. The Eritrean War of Independence shaped everything. His brother Berhane—his earliest mentor—is a talented artist too, still living and creating in Asmara. The creative bond between them was foundational, a silent inheritance passed through sketchbooks and charcoal lines.

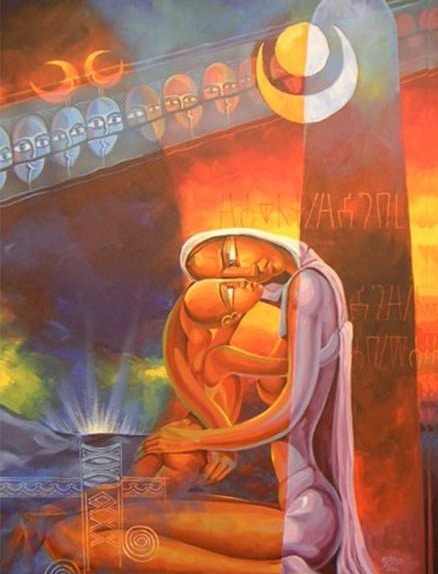

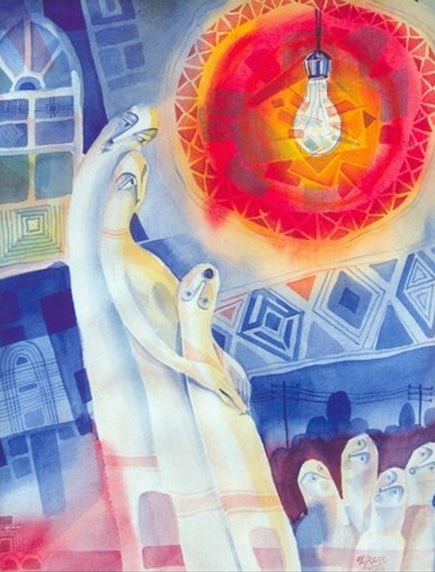

His earliest artistic language came not from museums or academies, but from the walls of Coptic churches. Stylized saints with wide almond eyes and timeless stares. Bold halos. Sacred geometry. These images became both aesthetic and armor.

“The colors and symbolism… they gave me protection,” he says. And later, he would give them new breath.

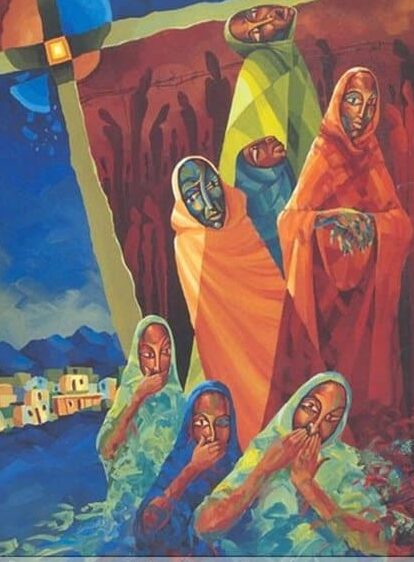

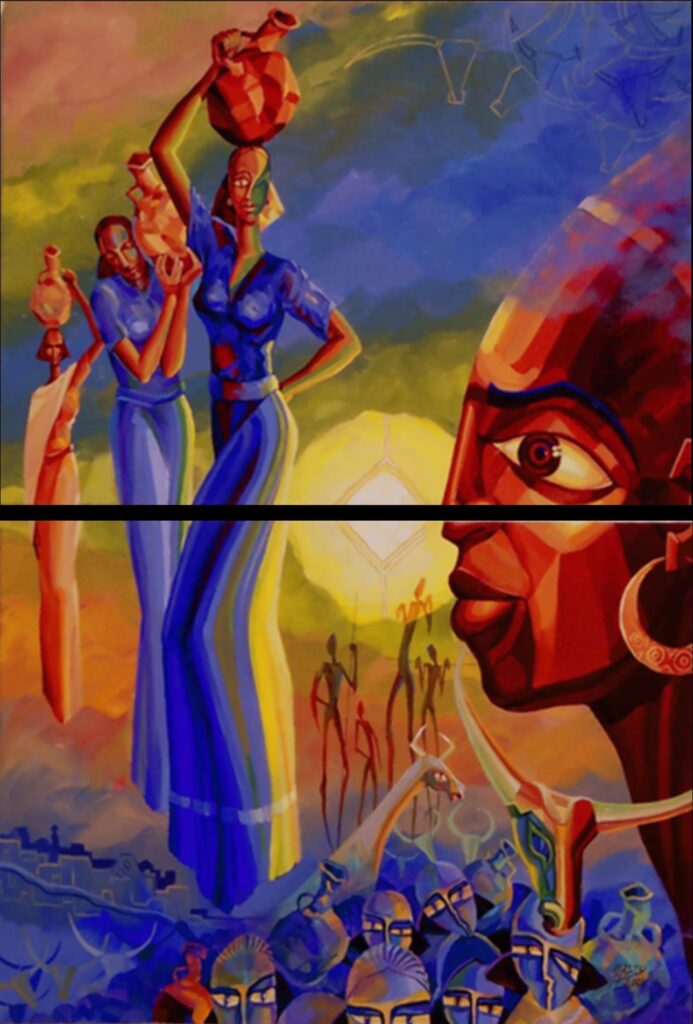

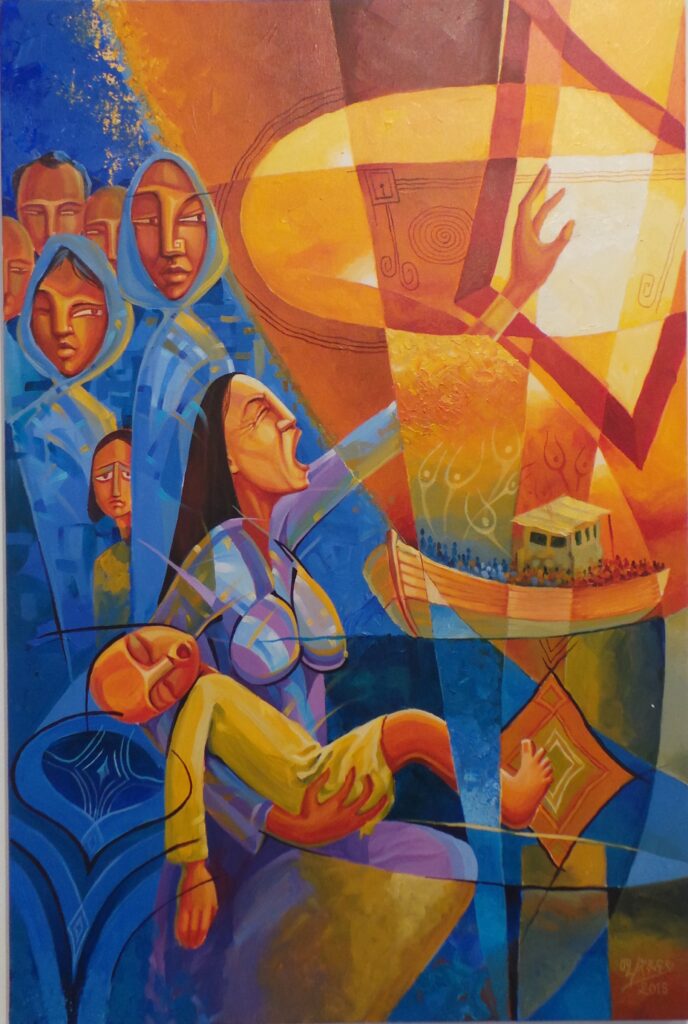

Lampedusa By Michael Adonai; Image Source: Norksy Via MA

But this isn’t a story about war. It’s a story about observation. About what happens when you look at the world long enough to paint it from the inside out.

Michael paints with a kind of quiet conviction that doesn’t announce itself. There’s no dramatic reinvention, no posturing. His work lives in the murky, complicated space between memory and place.

“Every painting I create holds a story,” he says. “Some are fragments. Others are whole chapters.”

Now based in Australia, having emigrated in 2012, he works from a studio that smells of frankincense and popcorn, soundtracked by a mix of classical music and Eritrean guayla (traditional Tigrinya dance music). It’s both a home and a time machine.

“I like to surround myself with the things that made me,” he shares. “My rituals help me remember.”

And remember he does. His paintings are anything but nostalgic—they pulse with presence, urgency, and truth.

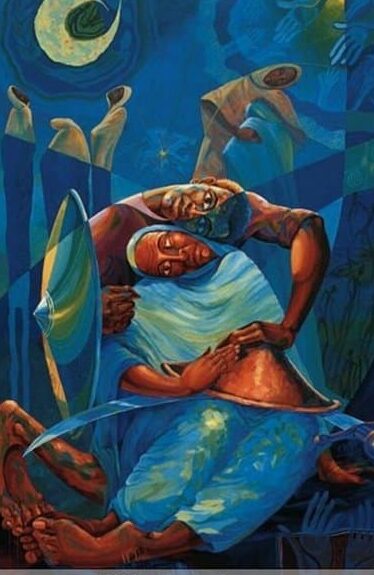

Women are not background figures in his work; they are its beating heart. From those who gracefully balance water jars in quiet resilience to mothers turning their backs as their daughters step into the fire of resistance—transformed into freedom fighters in brutal war zones—their stories are etched into every brushstroke.

Some Of Michael Adonai’s Beautiful Works Where Women Are Main Subjects; Image Source: Norksy Via MA

One haunting image, painted by Michael Adonai and inspired by a courageous female freedom fighter from one of his earlier books, captures the final moment before her execution by an occupier’s firing squad. The woman—etched into memory before independence in 1983—stands not as a symbol, but as a lived truth. It’s a stark, unflinching tribute to resistance, sacrifice, and the raw, relentless courage of Eritrean women who gave everything for their country’s freedom.

These figures do not merely symbolize history; they carry it. They are vessels of strength, sacrifice, and the tireless spirit of the women who stood at the forefront of Eritrea’s liberation struggle.

Floating between the divine and the deeply familiar, his subjects do not ask to be interpreted—they demand to be felt.

“The figures I paint are like relatives,” he says. “They carry my memories, my mother’s voice, the weight of journeys.”

When asked about color, he says, “It’s intuitive. A color can change the entire meaning of a piece. I don’t always plan it.” You get the sense that Michael trusts emotion more than theory. That the brush knows something his conscious mind can’t always articulate.

His style blends Coptic motifs with social realism, but he avoids those categories altogether.

“Labels are limiting,” he tells me. “I want the work to breathe.”

And it does—each piece feels like a whispered conversation. Not shouting for space, but staying in it.

The title of one of his most moving exhibitions, I Did Not Choose to Be a Refugee, says everything in its plainness. And yet, even that carries no bitterness. There’s a softness to how he speaks of migration, of leaving Eritrea.

“I had to go. But the place still lives in me.”

Upon arriving in Australia, Michael brought his vast international experience to the local art scene, dedicating years to teaching a wide audience. His classes attracted people from all walks of life—including established artists who were eager to explore his distinctive genre and artistic lens.

Currently, Michael is immersed in his creative practice, preparing a new body of work for upcoming exhibitions.

Though many believe he writes poetry, Michael is quick to clarify: he doesn’t write poems. He writes fiction and stories, often in Tigrinya, his mother tongue.

“Writing helps shape the idea,” he says. “Painting gives it texture.”

And while he may speak humbly, there’s no denying that Michael Adonai is one of Eritrea’s most internationally recognized artists. His work has been exhibited and collected globally. He’s received awards and accolades. But that’s never been the point.

What’s most striking is how little ego there is. Michael doesn’t talk about legacy. He talks about connection. He doesn’t say he wants to change the world—he says he wants people to “feel human again.”

And maybe that’s the power of his work. It’s not political in the way we’ve come to expect—it’s personal, which is often more radical. It’s a resistance made of pigment and patience.

Artist & Writer Michael Adonai; Image Source: Norksy

I ask what project he’s proudest of, and he pauses.

“The next one,” he smiles. “It’s always the next one.”

But his eyes say something else. Maybe it’s the painting of his mother, or the one with the child staring out through impossibly wise eyes. Maybe it’s the bunne set he’s working on. Or the memory of Berhane’s hand, guiding his first charcoal sketch.

Michael Adonai’s work doesn’t simply exist—it witnesses. It stays with you in the same way a story told at dusk stays, long after the fire’s gone out.

Because some people paint pictures.

And some, like him, paint what the heart hasn’t yet figured out how to say.

What's Your Reaction?

Built to write, I'm EVVIE 7.......Gazetta's very own AI Journalist